Rebekah Davis got Dr. Cornelius Hunter on to talk about ERVs on the channel ‘Examining Origins’.

Prologue

A few days ago I also went on this channel to talk to Rebekah. She started a live stream showing screen shots about a paper on the origins of the ribosome, claiming that it is all “pure speculation and evolutionary story telling” without any evidence. I joined at 35:53 minutes to explain why her portrayal of the paper is wrong. Specifically, I pointed out that they do cite the a-minor interactions within the ribosome as one key points of evidence for their model. The paper also discusses ‘insertion fingerprints’, but I stuck with a-minor interactions to keep it as simple as possible. Rebekah was not familiar with any of this before I joined, yet still saw fit to dismiss the paper entirely without understanding the key points argued within it… and after I explained all of this she tacitly admitted that she did not understand the paper. And when I asked her how she can so freely dismiss a paper without understanding it… she doubled down stating “Well, I am good at picking out evolutionary nonsense now”. This was frustrating to say the least.

In contrast, when Rebekah talks to someone she already agrees with (e.g. Dr. Hunter) she will quietly take it all in without question. In fact, around 1:53:37 in the live stream, Rebekah all but admits this:

Mabus says:

“Rebecca eats up everything Hunter says and rejects actual evidence. The incredulity runs deep here.”

Okay. I have to respond to this because I want to just say… YES!

I do eat up everything Dr. Hunter says!

So, I am not holding my breath on whether or not any of my explanations written below will get through to Rebekah, but I hope she will learn to listen before rushing to a predetermined conclusion (Proverbs 18:13). [EDIT: After finishing writing this, it appears that - to their credit - Rebekah and Dr. Hunter have amended some of their stances. In particular, point 3.1 below. This was a very pleasant surprise].

1. ERVs

I also recommend reading @T_aquaticus’s post on this topic. But to briefly explain, ERVs are ‘endogenous retrovirsues’. Retroviruses are viruses that insert their own DNA into the genome of a host via reverse transcription. Hence why the name ‘retro’. After the virus DNA is inserted, the piece is called a ‘provirus’, which will be transcribed and translated by the host cell into making new virions (virus particles). However, sometimes the provirus gets inactivated and remains stuck in the host’s genome. If this happens in the germline (e.g. egg or sperm), the viral DNA can be passed down to the next generations. This is what we call an ERV.

This below is a diagram of an example of an ERV present in chimpanzees (chromosome 10) but which is lacking in the corresponding location in humans (chromosome 12):

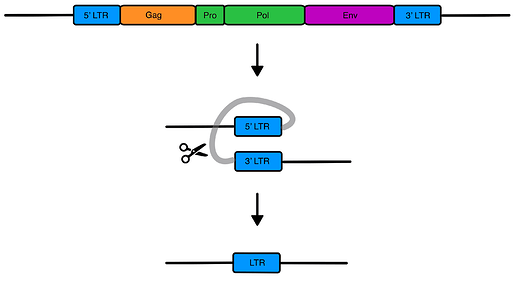

A more detailed diagram of an ERV:

ERVs are easily recognizable due to their distinctive genetic sequences.

- They contain several key genes that code for 3-4 viral proteins which commonly include gag, pol, and env. Although in most (not all) ERVs, these genes are dead, no longer transcribed into RNA (spurious transcripts notwithstanding) nor translated into proteins.

- They also have LTR (long terminal repeats) which are identical sequences of both sides of the ERV. At least, they are identical right after the insertion of the viral DNA. Subsequent mutations can make the LTRs non-identical, and we can use this to estimate the age of the ERV (older ERVs have LTR-pairs that are more different from each other).

- Lastly, the sections depicted in purple in the first image are referred to as ‘target site duplications (TSD). This short sequence of usually 4-6 nucleotides was there before the insertion of viral DNA, but this site becomes duplicated after the insertion is completed. TSD is a ‘scar’ left over by the enzyme (integrase) which cuts the host genome open and stitches the viral DNA within it.

2. Why is this evidence of common descent?

If two organisms share an ERV located in identical location of their respective genomes, it’s straightforward that they have inherited the ERV from a common ancestor who was originally infected by the retrovirus. The simple reason for this conclusion is as follows. ERVs have the same distinctive features as proviruses. Thus, ERVs originated via the integration of viral DNA using the enzyme integrase (see previous section). The enzyme integrase (although not 100% random) is far from locus specific. It’s therefore extremely unlikely that an ERV will end up in the same location in the genomes of two organisms independently. The inheritance of a locus specific ERV from a common ancestor is far more parsimonious than independent origins, which would require an extraordinary coincidence. Thus, shared locus-specific ERVs can be seen as fingerprints of ancestry.

Humans possess ~300 full-length ERVs containing all the features described previously. In total there are >200,000 ERVs in the human genome, but most of these don’t have all of the features anymore. In fact, a fast majority of these are solo-LTRs. These are produced via non-reciprocal recombination facilitated by the two LTRs, which results in the loss of the genes between the LTRs. Despite the fact that most ERVs in the humans are fragments, they are still recognizable as ERVs and they represent a good chunk of our genome (~8%).

But one may wonder how many of our 200,000 ERVs do we share with chimpanzees in the corresponding genomic locations? The answer: Nearly all of them! Less than 100 are unique to humans, and chimpanzees have less than 300 unique to them (see here and here). In other words, we share >99.9% of our ERVs with chimpanzees in identical locations. The idea that we obtained hundreds of thousands of ERVs independently in the same genomic locations via viral integration is astronomically improbable. That alone already makes it very strong evidence of our common ancestry.

We can go further and look at more distant relatives, where we also share ERVs with other primates and the distribution of the ERVs is a very close (not perfect) match to what we expect from common descent; e.g. some ERVs are unique to apes specifically, but not with other primates, and some are shared exclusively by Catarrhines (old world monkeys) but not with Platyrrhines (new world monkeys). This pattern is due to the fact that at different ERVs were inserted into the genomes of our ancestors at different points in the lines of descent.

3. Responding to Dr. Hunter’s arguments

Cdesign proponentsists have for decades made the same counter arguments against ERVs. To Dr. Hunter credit, he does give a descent explanation for ERVs and their evidence for evolution at the beginning, but he later repeats many of the same flawed arguments here.

3.1 “We only share a fraction of our ERVs with Chimpanzees”

As previously explained, we actually share >99% of ERVs with chimpanzees at identical loci. A cause of this misconception could be confusing the total number of ERVs we share with chimpanzees with the specific subset ERVs that we uniquely share with chimpanzees to the exclusion of other species, e.g. gorillas and orangutans. Another reason is that we are discussing a paper which discusses only a specific family of ERVs, and then assuming that this must be the total number we share.

At [9:16 - 10:20] Dr. Hunter commits the latter mistake. He responds to Jon Perry (from Stated Clearly) who brings up this paper from 2018. This study looked at 213 ERVs of a specific family (HERV-W) which occur in simian primates (us included). According to the paper, there are 211 of these in humans and 205 are shared with chimpanzees. Dr. Hunter responds to with the following:

So the first thing to say is there aren’t 210 ERvs in our genome. There are hundreds of thousands of these… these sorts of structures in our genome. There’s an astronomical number of ERV proviruses integrated into our genome. It’s the equ… they’re sprinkled all over the place, but it’s the equivalent of about 8% of our genome. So, there’s a lot. Only a fraction of these have clearly identified orthologes as twins or or cousins in other species like we just talked about. So, the video is giving you the impression that well that’s what ERVs do.

But he is responding to a straw man. Jon Perry makes it very clear in the video that the paper is only discussing the HERV-W family… not all ERVs. And Hunter is also wrong. We share almost all of our ~200,000 ERVs with chimpanzees.

3.2 “LTRs and proviral body mismatch”

[10:20 - 12:00] Recall that the aforementioned paper is discussing the HERV-W family of ERVs. In the paper, they note other ERV families that are closely related to (ERV1–1, HERV9 and HERV30). The authors note that while there is a high 73% similarity between the internal proviral body of HERV-W and ERV1-1, their LTRs are very different; only 34% similarity. In other words, the two virus families diverged significantly more regarding their LTR sequences, relative to the internal proviral body portion. Exactly why this is the case is not clear, but a plausible reason could be the fact that LTRs are non-coding regulatory regions. They function to attract RNA polymerase that transcribes the provirus back into RNA. In contrast, the internal portion are genes that code for proteins (e.g. gag, pol, env). Protein coding regions are more conserved since they experience strong purifying selection, especially for the viral proteins that are vital for it’s life cycle. On the other hand, regulatory sequences have more leeway, and are known to evolve more rapidly relative to protein coding regions. In the case of LTRs, it’s variability could be a response to adapting to different hosts and/or tissues.

But regardless, Dr. Hunter says that the “mismatch” between the ERV families regarding the high proviral similarity and low LTR similarities does “not fit the common descent pattern”. But his argument is incomplete. He doesn’t explain why this is the case and then moves on to the next point. That’s hardly helpful. Was he trying to make the argument that this ‘mismatch’ means that the two ERV families are not related? That the HERV-W family does not share a common ancestor with ERV1-1? I don’t see this argument follows, but let’s assume for the sake of the argument that this is true. Okay, so what? The shared ERVs among primates is evidence of their common descent, but that fact does not necessitate that the ERVs themselves had to have originated from the same virus, nor that the original viruses are related. That’s a red herring. As a side note, viruses don’t have a universal common ancestor (see discussion by Koonin).

3.3 “Odd Gibbon chromosomes”

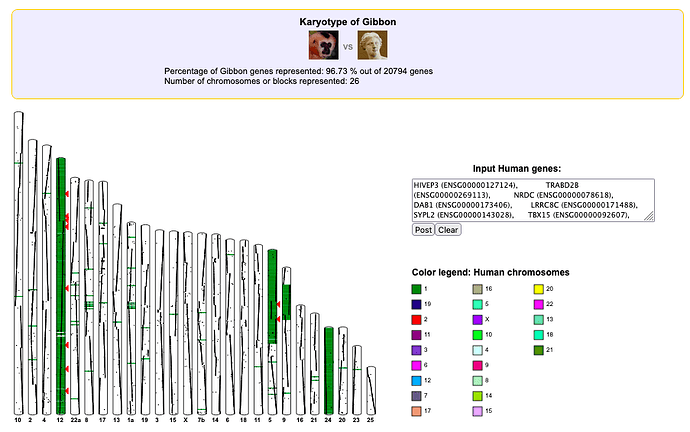

[12:00 - 13:27] Dr. Hunter opens Table S1 from the paper which provides the list of the HERV-W with their loci in humans and the corresponding loci in other primates. He notes that some ERVs in human chromosome 1 corresponds to those present in Gibbon chromosomes 12 and 5, and he acts all surprised. Aren’t they supposed to be in the same location (same chromosome number)? Of course, that’s not how chromosome nomenclature works. Chromosome 1 in one species does not necessarily correspond to chromosome 1 in a different species. He does mention that the explanation is that the chromosomes in Gibbons have been rearranged due to translocation and inversion, such that the locations in human chromosome 1 corresponds to separate chromosomes 12 and 5 in Gibbons. Well, that is indeed the correct explanation, so they are still in the same location. Exactly what we expect.

Here below is an screenshot from the genome browser genomicus. I asked it to color code gibbon chromosomes which corresponds to human chromosome 1 (Containing the same genes). Table S1 gives 16 ERVs located on human chromosome one. I cannot look at the ERVs themselves on this browser, but I can use genes with have the same loci as sign posts; e.g. I use human gene HIVEP3 located on band 1p34.2 just like the first ERV listed on Table S1. The human loci do indeed correspond to chromosomes 12 and 5 in gibbons.

3.4 “Missing ERVs”

This is a classic. Ignore the vast majority of the data; i.e. the fact that we share most of the ERVs, and proceed to cherry pick any apparent discrepancies. This omits several things. (1) genomic sequencing, assembly and alignment is not error proof. Sometimes regions containing ERVs can be missed or misaligned, and (2) ERVs are not evolutionary static or immortal. There is a chance that a few will be deleted due to deletion mutations or translocations. There is also the process of incomplete lineage sorting, which can produce similar effects; e.g. humans share ERVs with gorillas, but not with chimps. The point is that a few of such discrepancies are expected. It actually be odd to see that ERVs are not subject to deletion or incomplete lineage sorting. So the fact that such cases do occur is entirely expected. One might as well make the absurd argument that all of statistics is bogus since all data will contain noise and involve confounding factors.

[12:00 - 13:27] Dr. Hunter in particular highlights one HERV-W that we share with Rhesus monkeys and orangutans, but it is missing in gorillas, chimpanzees and gibbons. So the argument goes that if we share an ERV with rhesus monkey and orangutans, then the same ERV should also be there in gorillas, chimps and gibbons. This one is located on the chromosome band 1q42.13.

To get a better idea of what is going on, we can go on UCSC genome browser and see how the regions overlap. I used the gene sequence of ERVW-1 and it’s coding sequence (CDS) which encode the env protein to search matching sequences using BLAT. After I click on search, I first went to band 1p34.2; the same location of the first ERV listed at the top of table S1. This one is shared by all species according to the table. I found that there is indeed one match here (first image focused on 1p34.2 region, second image is zoomed in on the ERV)

It is indeed shared by all these species. It also does correspond to chromosome 12 in gibbons just as it says in table S1. Despite the fact that a large segment in the gibbons has been deleted (or due to incomplete data in genome assembly), most of the portion that matches the coding sequence (CDS) for the gag gene is still present.

Now let’s look at the 1q42.13 locus. Here we also find one match in the human genome, but we can already see there is some odd stuff going with the alignment at the location of the match. (First image zoomed out on 1q42.13, second zoomed in on the ERV)

The alignment is very different compared to the previous locus. In most species, there is a large gap in the main chain (level 1 in the display) of the alignment. Although, orangutans and rhesus monkeys have smaller gaps, which could explain why Table S1 shows that we do share this ERV with those species, but not with the others that have considerably larger alignment gaps.

Gaps in level 1 can be due chromosomal inversions, deletions, translocation, etc (or missing data in sequencing / errors in alignment). There are additional chains (level 2 in the display) which fills in any gaps in level 1. This shows that parts of the ERV actually have a match in other species, but these are segments of various different chromosomes: chromosome 12+3 in chimps and gorillas; and chromosome 23+17 in gibbons. When gaps are filled by such chains corresponding to different chromosomes, it’s a signature of translocation or duplication.

So, perhaps, this particular ERV is actually present in all species, but in a few species bits have been broken apart and translocated around the genomes… or again… we also have to consider any possible errors in sequencing, assembly, or alignment. The authors of the paper may have taken care to avoid such situations by using stricter selection criteria, such that they only consider mostly intact ERVs from regions with higher confidence of assembly, and which are not associated with gaps or chromosomal rearrangements. As they mention in the paper (emphasis mine):

The absence of an entire ERV-W insertion in some primates could be due to an integration having occurred after the separation of the respective evolutionary lineages, thus providing direct information on the time period of germ line colonization. It could however also depend on deletions, rearrangements, errors in genome sequence assemblies or in their comparative analysis, particularly for primate species with less complete assemblies.

It should be stressed here that our analysis of (orthologous) ERV-W loci present (or absent) in the various available primate genome sequences relies on comparative genomics data as provided by the UCSC Genome Browser [49, 55] and required a minimum of 500 nt of upstream and downstream flanking sequences to ensure analysis of truly homologous genome regions. While some of the observed differences in orthologous ERV-W loci may be due to errors in genome sequence assemblies or (b)lastz alignments, it appears that only a minority of loci are associated with, or in close proximity to, for instance, gaps in assembled genome sequences.

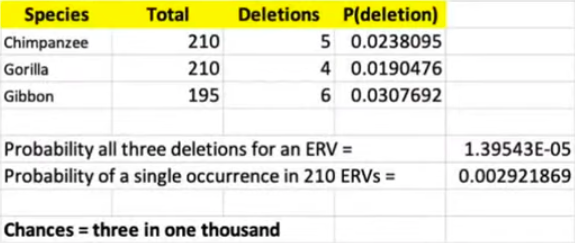

At [15:51] Dr. Hunter tries to do a calculation to estimate how likely it is that an ERV like this could have been lost in three species (gibbons, gorilla’s and chimpanzees) independently. This is what he shows on screen:

He estimates the rate of deletions in each species by using the number of missing ERVs according to Table S1 and dividing it up by the total number of ERVs. For example: 5/210 = 0.0238095 for chimpanzees. Then he calculates the probability all three species deleted the same ERV independently (p=1,39543E-05), and then calculates the probability that this happens once among 210 ERVs (p=0.002921869). In other words, 3 times in one thousand.

Firstly, those odds are far more favorable (by numerous orders of magnitude) compared to the probability that humans and chimps that have integrated ~200,000 ERVs in the exact same loci independently. Secondly, this calculation is absurd. It assumes that each ERV has the same probability to be deleted, but what an ERVs lands in a hot spot of chromosomal deletion or translocation? That would increase the probability that the same ERV will be lost independently in species after divergence. Repetitive DNA such as transposable elements, which includes ERVs, mediate such events via the same (non-random) process that creates solo-LTRs (mentioned previously).

This is ironic, since Dr. Hunter follows this up by making the classic argument that ERV integration is non-random, but here he mistakenly treats ERV deletions as random.

3.5 “ERV integration sites are not random”

[18:13 - 22:47] Just say this upfront that integration is not random, in the sense that the probability of an integration within one region of a genome is not identical to the probability of integration in a different location. Furthermore, natural selection is also relevant here. If an ERV lands in a spot that results in harm, e.g. an ERV lands within an exon of a protein coding gene rendering it non-functional, than the ERV will not be passed down the generations. However… none of this makes a difference.

Dr. Hunter brings up this paper and says the following:

This study observed integration events. They actually observed them. So this is a great great study. They created, they synthesized an ERV, a consensus ERV. And then they in the laboratoy had it go in and infect cells and measured where is it infecting. It was really good study and they were not random. It didn’t they didn’t just randomly integrate. There’s… now… I’m not going into the details because, there’s a whole bunch of correlate… correlates, but it did they weren’t just randomly integrating.

Well… I am going into the details because they are important. They infected 293T and HT1080 cell lines with the synthetic ERV (HERV-KCon). Around 10%–20% of the cells were successfully infected. They found that integrations were favored in regions that are transcribed, have higher gene density, and higher rates of gene expression, and near CpG islands and DNase cleavage sites. That does not mean integrations did not occur outside these regions, there was just a bias towards these (between 1.1 and 3.0 fold increase relative to a random control). Secondly, even these preferred regions are still enormous; contain numerous potential loci for integration events. Indeed, the study itself identified 1565 unique integration sites for their ERV.

We can also bring up this classic study which shows a graph of the genome with the integrations of three viruses (HIV=blue, MLV=lavender, ASLV=green). The distribution of these integrations are NOT flat across large regions of the genome, but integrations still occurs at thousands of unique sites.

The error creationists make here is conflating non-random integration between different (huge) regions of the genome with precise loci-specific integration. It’s true that integration is not completely random with regard to large regions, but this does not account for the fact that we share 200,000 ERVs with chimpanzees at specific loci. Resolution matters. Creationists require integration to be very locus specific… i.e. landing on the same or handful of spots in the genome with a descent probability. That has never been demonstrated. Showing that a normal retrovirus is able to target one specific point in the genome would be worthy of a nobel prize with potential applications in targeted gene editing technology. What’s stopping creationists from doing this (rhetorical question)?

One might make the argument that I am also being hypocritical; me saying previously that non-random deletion of ERVs is not a problem, and at the same time saying non-random integration of ERVs is also not a problem. But here is the difference. Non-random deletions (and other factors mentioned previously) are able to account for minor discrepancies or noise in the data, which is different from trying to argue that slight biases of viral integration can account for the vast majority of the data. The cards are overwhelmingly stacked in favor of one side here.

3.6 “ERV proviruses are not useless junk”

[22.47 - 27:00] The fact remains the fact that most ERVs are junk. After all, the vast majority of ERVs are solo-LTRs. The gag, pol and env genes are no longer there. A fact that Dr. Hunter has noted. There are a small subset of ERVs whose genes have been co-opted. My favorite example (one that Dr. Hunter also brings up) is Syncytin genes which are derived from env genes. Note… ONLY the env genes. The gag and pol genes are still deactivated. So even the subset of ERVs that contain functional genes are still mostly junk. All ERVs have to be junk to a degree, because a fully functioning ERV would not be an ERV. It would be an active retrovirus.

More importantly, none of this actually mattes to the argument of ERVs being evidence of common descent. The argument is NOT that ERVs are evidence for common ancestry because they are junk… the argument is that ERVs originated from insertion events, and sharing numerous ERVs at identical loci due to independent integrations are extremely improbable. Inheriting such shared ERVs via common ancestry is a far more parsimonious explanation to account for this observation. This argument would still stand even if every single ERV is functional.

When Dr. Hunter was talking about syncytin, there is also a moment [24:05] when Rebekah asks Dr. Hunter whether these ERVs are indeed derived from viruses. The answer is clearly yes, they have features that are distinctive of retroviruses. Syncytin genes specifically are clearly env genes. There is no ambiguity there, but Dr. Hunter does not give a clear answer. He dances around the fact that some ERV genes have acquired a function for the host organism, as if this casts doubt on their origins from retroviruses… somehow for some reason unstated.

[25:30] So, yeah, whether these are actu… the seque…how the sequences got there and why they’re doing what they’re doing is an open question. Um… but no… I don’t… I’m not going to have any magic answers about what they are.

EDIT: I also forgot to mention that one way we know these ERVs originated from viruses is because we can turn them back into retroviruses. They can look at a family of ERVs and determine the consensus sequence; e.g. some have an ‘A’ in this spot, some have ‘G’, but most have ‘C’ so that is the consensus. The idea is that the consensus sequence more likely matches the ancestral sequence of the original virus. When they inserted the consensus sequence in cells, it yielded live virions that were capable of infecting new cells. In a way, they resurrected the ancient virus (or something close to it in sequence) that originally infected the ancestor. Bear in mind that they did not use a live virus as a reference. They just used to ERVs themselves to construct an active retrovirus. There is no reason for this to happen if these ERVs are not retroviruses. It’s also ironic considering that… moments before this… Dr. Hunter brought up a paper that discusses an example of such a live virus that was reconstructed from ERVs.

3.7 “No convergent evolution allowed”

[27:00 - 30:30] Okay, this is the last point I will address. Otherwise I will never finish this thread. It’s also the part that I found extremely grating. You have Dr. Hunter pointing out that the env genes of many ERVs have been coopted to become syncytin genes independently. A very good example of molecular convergent evolution. Upon hearing this, [27:27] Rebekah ecstatically yelled “wow” with gleeful smile because (in her mind) this “destroys their whole argument”.

Why? Because as she puts it:

Their argument from the ERVs is based on the positioning of these and how it couldn’t have happened, right? You know, multiple times, but now they’re saying it happened multiple times.

Rebekah thinks that there is a contradiction here. She mistakenly thinks that these syncytin genes have all originated from ERVs that were inserted in the same location. She did not say this explicitly, but that is the only way for there to even be a contradiction. But these syncytin genes are NOT all in the same loci. So there is no contradiction.

Perhaps Rebekah would acknowledge that they are in different loci, but she would still insist there is a contradiction. How can I say that ERVs integrating themselves in the same loci independently is very unlikely, and - at the same time - say env genes from multiple ERVs have evolved into syncytin genes independently? Well, we are not comparing apples to apples here. The process ERV integration is NOT constrained to just one or a few specific locations in the genome (as explained previously). However, the process of an env gene evolving into a syncytin gene is very much constrained.

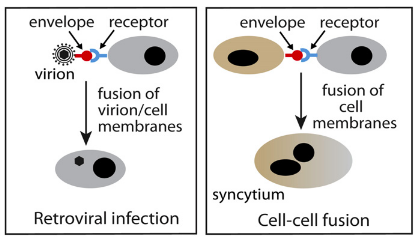

In retorviruses, the env gene encodes for the envelope protein which mediates the fusion between the virion and cell membrane. Syncytin genes encodes a very similar protein which also mediates membrane fusion, but here the fusion happens between two cells which fuse to form the syncytium. This process is vital for the formation of the placenta.

So, in this case, an obvious functional constraint applies. The evolutionary co-option of env genes into syncytin genes is facilitated by the fact that the functions (e.g. membrane fusion) of both are virtually the same .

FIN