Not sure to understand all your points here. But you have to consider that the usual view in ID circles regarding the rarity of functional sequences concerns protein sequences not regulatory ones.

That does appear to be the case, at least with respect to high expression levels. However, there is counterintuitively an even higher fraction of DNA that elicits transcriptional activity by eukaryotic initiators, than in prokaryotes. Though the expression levels are lower on average.

I think you owe us a few answers before you ask any more questions.

Interesting. Would also make sense when you think about the fact that eukaryotes have way more transcription factors and corresponding TF binding sequence motifs, such that there is a higher likelihood that one or a few activators will bind onto a random sequence and initiate transcription… at least occasionally. As you said, the expression levels are much lower. For higher levels, the combined effect of many TFs are likely needed, which means that the multiple binding sites for high expression levels is less likely to occur spuriously.

Which is rather odd since regulatory sequences are arguably more important to evolutionary change than protein sequences. The differences between humans and chimpanzees are going to be more to do with regulatory sequences than proteins.

And it means that this apparently junk DNA has a very low information content and is often largely redundant (which makes the “junk” label reasonably applicable to large portions of it).

Probably, but this has nothing to do with the proportion of functional sequences in sequence space in the two categories, ie, protein vs regulatory sequences.

It still makes things harder for ID. And it still isn’t very plausible.

Consider further, if disabling a gene produces useful regulatory sequences, there are more ID arguments that suffer.

What metric would you suggest is reasonable to assess the magnitude of that proportion? Is it possible for this metric to return anything other than 100% for any naturally occurring genome? If yes, then why should we expect its results to be any more consistent with the entire-genome-is-functional-actually hypothesis? What does your suggested measuring technique offer, in terms of data assessment suited for predictive modeling, above or beyond what is provided by established methods?

Ok, so this is super interesting. Let me see if I can understand the implications here. I’m going to explain then to you as if I know what I am talking about, and then you (all) correct me about the things I get wrong.

So, if the genome size varies significantly within not just a species, but a subpopulation of that species, then for that species at least, the amount of material that is non protein coding and yet still functional must be low. This must be true because a particular sequence or even set off sequences cannot be doing anything when it doesn’t matter whether they are there or not.

Further, in this study it is not fair to say that the"junk" isn’t doing anything in that it is lengthening the DNA and thereby making the replication and flowing of the plant slower. This does have an effect which can be selected for, because you may want slower flowering at higher altitudes, and faster flowering at lower altitudes. However, that does not support the position that the DNA is functional, but rather that the overall amount of “junk” itself can sometimes serve a function.

If the amount of junk can be observed to be selected for, in a circumstance where the content of that junk is not observed to be selected for, then it is strong support for the argument that it is junk. When you select for junk, you get junk, and it does what junk does.

It can’t be other than junk when it is readily incorporated and discarded. Its content evidently doesn’t matter, and selection would have no way to manage that content in such a scenario, do it doesn’t even make sense in a theoretical basis that it would matter. In the circumstances, it must be random.

Ergo, it must be the case that large amounts off junk DNA do exist in at least some genomes. Consequently, it cannot be the case that all genomes are intelligently designed with fully functional genomes.

That is, it is true that large sections of the genomeb which do not appear to have function can and at least sometimes are without function. this has been observed. However the converse, where large sections of the genome (in unconserved regions, other than instances where new functions are emerging because of recent evolution) which are apparently without function actually having function has not ever been observed.

Notably, to anticipate an objection, this does not suggest that there are not undiscovered bits and peices of regulatory code scattered within the non coding regions, or that we won’t continue to find such genes, but rather that there is no evidence that the large portions of those regions (as would be required to reach 80 or 90 prevent functionality for the genome as a whole) have function, and that there is evidence to suggest they don’t. Thus, the evidence as it stands now suggests that the majority of the non-coding regions are not functional on a balance of the probabilities (that is, more likely than not).

So some number that you don’t know is either greater or smaller than some other number that you don’t know.

Paging Edmund Blackadder…

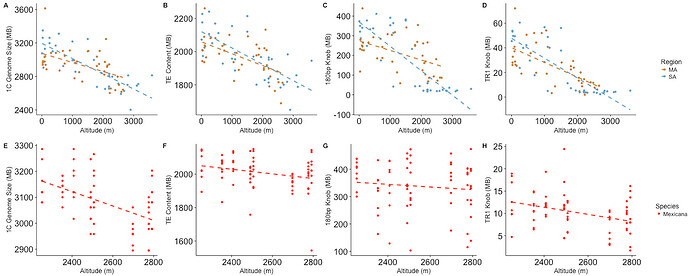

Yes, but according to the authors, it seems that these intra species variations in genome size are adaptive, hence functional !

If that’s what you mean by functional, welcome to the “evolutionist” camp. It’s nice here. We have cookies.

Not really, no. The loss of various types of repeats appears to be adaptive in some environments. That’s what the paper shows.

So, just to be clear… In your interpretation, the authors of the referenced article are saying, that… genes a sort of a plant is missing have a function in said plant sort? Would you kindly quote what part of the article specifically sounds anything like such lunacy?

To be fair, bulk sequence functions produce a sort of intermediate between functional sequences and junk. Point mutations aren’t under selection, but indels might be, at least a little bit, for such sequences.

Add images

To the extent that is all Gill means by"functional" there is no daylight between us. It’s only if he intends to go farther that he swims in shark (ie scientist) infested waters.

Basic questions may sometimes be useful!

Anyway, it seems to me that you are necessarily assuming common descent for these ~ 90% that lack conservation. So the question now is what evidence do we have for this assumption ?

Anyway, it seems to me that you are assuming common descent for these ~ 90% that lack conservation. So the question now is what evidence do we have for this assumption ?

The one and only viable scientific theory of biological descent is that the replication of DNA and passing it on to new organisms is how it occurs. The way to test whether two persons are siblings or cousins without man-made documentation is by comparing their genomes. The entire point of the study of genetics (hint’s in the name, for crying out loud!) is to understand – with predictive models, as it were – how descent works. To put it in my own earlier words:

Just to be clear, you are aware, that DNA is literally the substance of inheritance, right? Because the only way for DNA to not be an indicator of relatedness is for it to not be that. There is no third option. There is no way for DNA to both be what carries genes and for it to not be that.

Likewise, the entire reason DNA is ever brought up either by creationists or their scientifically literate interlocutors, is that both understand that it is how nature facilitates descent, and how we recognize it as such. If this is something we can all of a sudden no longer agree on, then there is hardly any matter of biology we can meaningfully discuss going forward. On the other hand, if this is something you genuinely didn’t understand or accept throughout this entire time, then I second John’s sentiment about this being a rather late point in the conversation to be bringing up such a fundamental disconnect.

Anyway, it seems to me that you are necessarily assuming common descent for these ~ 90% that lack conservation. So the question now is what evidence do we have for this assumption ?

The same evidence as for the conserved part. The nested hierarchy.